Medieval Well, Astley Ainslie Hospital

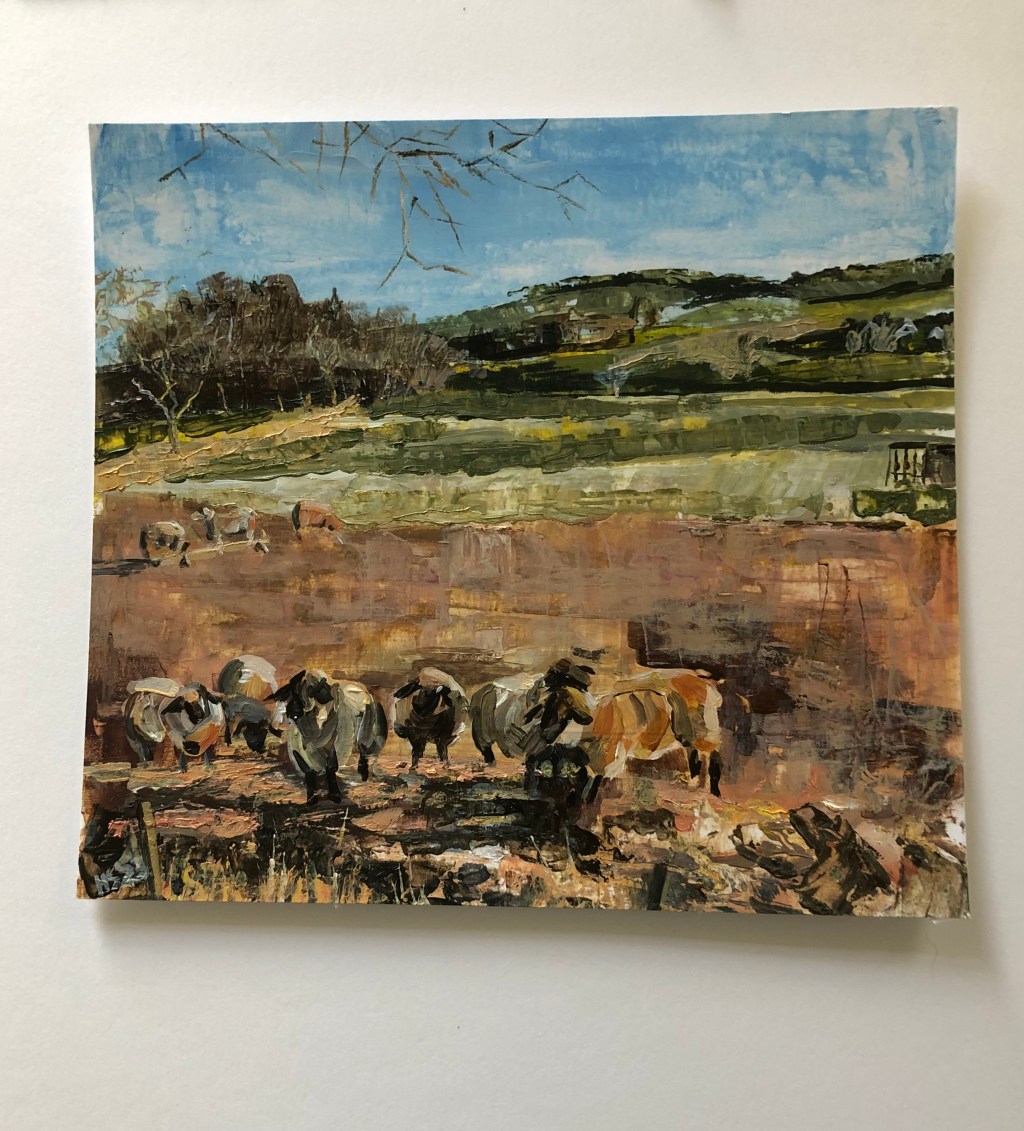

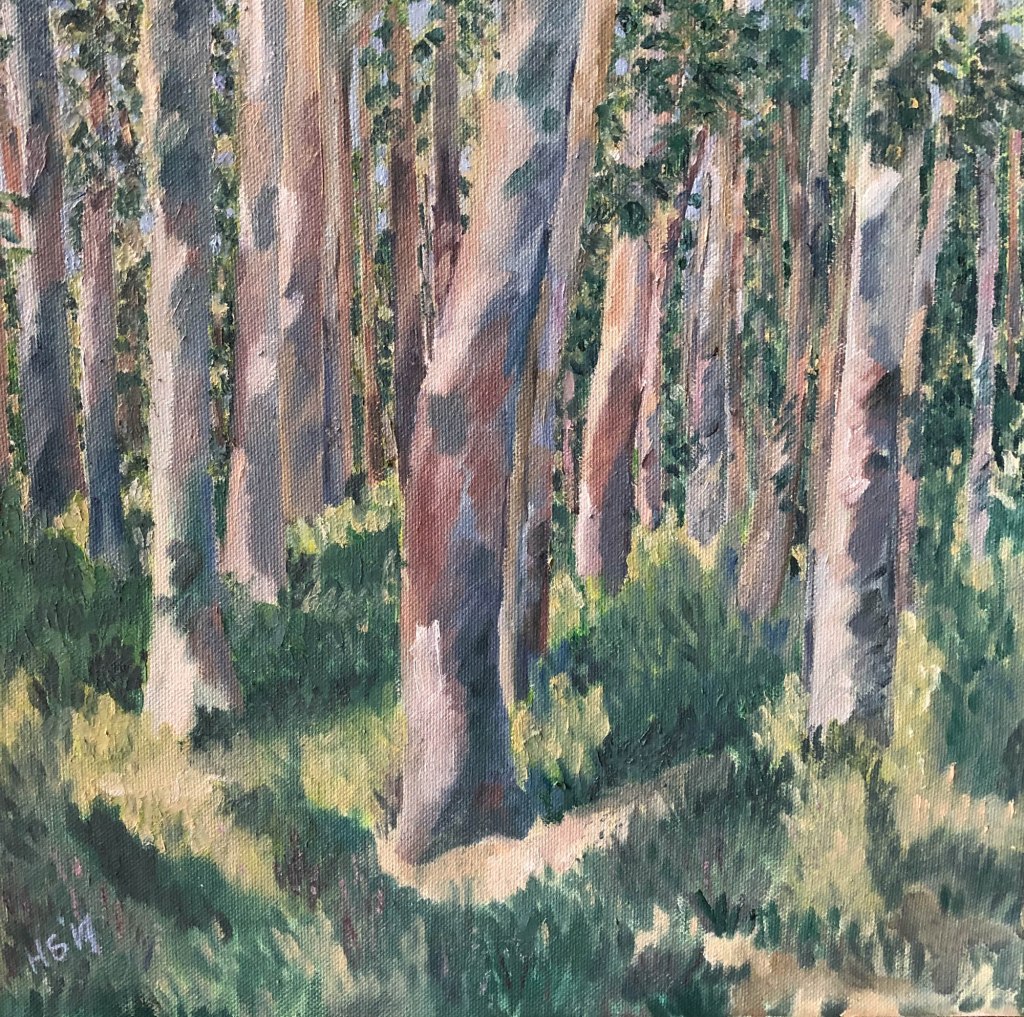

Helen’s depiction of a medieval well on the grounds of a 1930s hospital in South-Central Edinburgh has been undertaken during her continuing spell as a member of staff working there. The well was built for patients who had unfortunately contracted bubonic plague, which was swift in its destruction of communities and families across Europe and Asia in the middle of the 14th century. A number of ancient wells can be found on the hospital estate, sometimes hidden by the foliage and trees that are so plentiful there. The beautiful grounds of this hospital, which started life as a rehabilitation facility, contain an impressive variety of trees including cherry and apple, firs, chestnuts, oaks, along with huge rhododendron bushes and a little cemetery for the pets of patients. There is to be found an assorted mixture of buildings of Victorian and 1930s architectural styles juxtaposed with 1970s brutalism, jostling with wooden huts, all set in the peaceful context of the Grange area in South Edinburgh. Helen’s painting deftly captures an aspect of this tranquillity, lightly rendered in greens and browns, deploying a delicate colour palette.

The bubonic plague arrived in Edinburgh during the middle of the 14th century and thrived in the overcrowded and unhygienic conditions of the medieval town. The outbreak in the form of the Great Plague of 1645 killed many thousands of people, accounting for half the population of the city, and finally disappeared two years later. This devastating event has been marked by few memorials, so this well is a valuable reminder of the dreadful loss of life from a lethal, infectious disease in 17th century Scotland.

Wells have long played a vital role in city’s history: Edinburgh citizens used to have to queue in times past for water, using any receptacle they brought along. In a cruel twist of fate, the pumps could also at times serve as a generator of disease, as was brilliantly demonstrated by John Snow in respect of the connection with cholera for those using the Broad Street Pump in London. Epidemiology was born that day and now is practised on the grounds of the hospital. Indeed it is presently governing our lives during the coronavirus pandemic, albeit diluted by political and economic concerns.

Wells have a symbolic function in art: they represent fruitfulness, hope and nourishment in dry deserts of life. They offer replenishment for the soul in sparse and difficult times, on top of the promise of life-giving water. Examples of this can be found scattered throughout the works of many artists. These include the likes of Paolo Veronese’s ‘Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well’ from 1585, Nicolas Poussin’s ‘Eliezer and Rebecca’ from 1648 and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s ‘Rebecca and the Well’, painted in 1838/9. More secular treatments can be found in Franz Xaver Winterhalter and his ‘Young Italian at the Well’ from the 1860s, Camille Pissarro and his ‘Women and Child at the Well’ from 1882, and Paul Signac’s more modern take in his ‘Women At The Well’, painted in 1892.

Wells have also featured in the works of artists as diverse as Antonio Bellucci, Holman Hunt and Diego Rivera. Their studies and approaches are varied and distinctive in character. In the works of these artists they appears to function in a number of ways. Some feature a woman as an essential part of the story, as in the case of biblical depictions. The symbol of fruitfulness and the connection with the female presence and female body can be readily perceived. This thread runs through from classical depictions of the likes of Veronese to the more modern interpretations of the PreRaphaelites like Hunt and others to follow. In this way the well has functioned as a useful motif and metaphor for inspiration and fruition, sometimes even as a symbol for temptation.

The parallels between the world of medieval wells and the contemporary world and the parallel of bubonic plague with the current pandemic of coronavirus are too tempting to resist here. One can only feel deep empathy and sympathy with the plague victims, so often so nameless and identity-less victims in the past no longer remembered. The bubonic plague lasted for centuries and was widespread across Europe and Asia, spread by the humble fleas on the ubiquitous rats brought by ships and other forms of transport in medieval times. The parallels between our modern world and medieval worlds are also intriguing to contemplate upon. Today’s pandemic has provided many locked-down citizens the chance to reflect on such parallels with a disease-ridden world thought to have been vanquished.

Helen’s artwork thus provides the viewer a thought-provoking picture, deeply moving in its way, and very apposite in the face of the pandemic shutting down the modern world. The viewer may well be tempted to ask what lessons one might draw from such tragic and universal events between these two separate yet intimately connected worlds. He or she may well wish to offer a moment of empathetic sympathy for the victims of the Great Plague and their modern counterparts during a stroll through the charming and pleasant grounds of this hospital.

Patrick McConnell

June 2020

Leave a comment